The revenge of the ages

Rasmus Sørnes was denied clockmaker apprenticeship. Then he went on to make some of the world’s most complicated clocks.

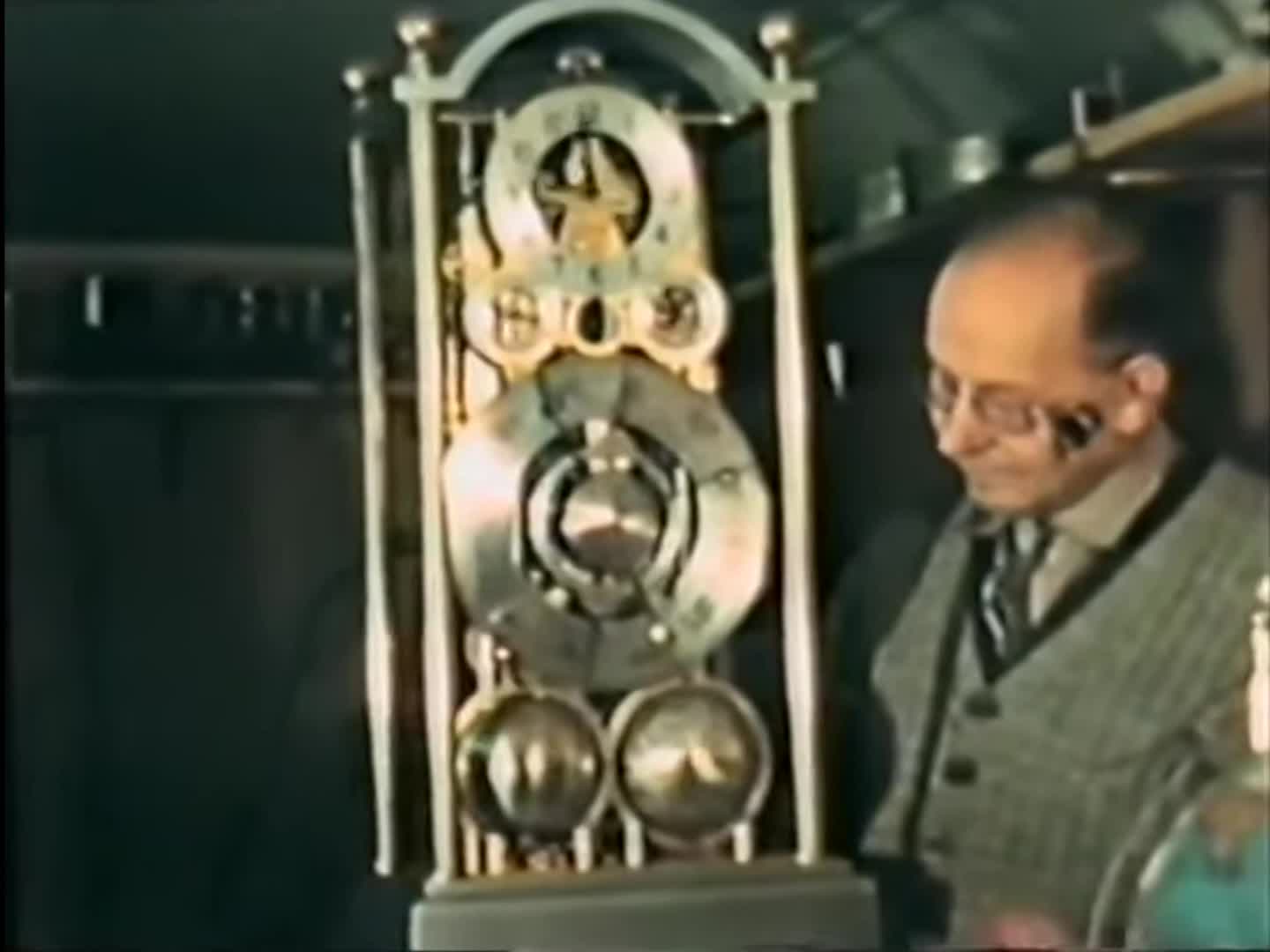

In 2002, a very special clock goes under the hammer at the renowned auction house Sotheby's in New York. It’s gold-plated and can tell the correct time for over 25,000 years.

The clock was made by nothing but a pair of hands and one intellect. According to the seller, The Time Museum, this is one of the world's most complicated clocks.

At the top is a large dial with star signs. Underneath are many small dials that show the movements of the sun and moon, the time, low and high tide. At the bottom, the clockmaker found room for two small globes.

Who builds something like this? A Norwegian farmer's son lacking any training in clockmaking.

When the auctioneer raises the hammer and hits the table three times, the sale amount is $295,000. The price corresponds to NOK 2.3 million in today’s money.

A Norway with several time zones

Rasmus Sørnes is Norway's unknown Gyro Gearloose. He made four astronomical clocks. Two of them are considered among the world's most complicated. In addition to the clock that’s being sold in New York, there is an almost identical one at the Borgarsyssel Museum in Sarpsborg.

INVENTOR: Rasmus Sørnes did not gain the title of clockmaker, but learned the trade nonetheless.

Foto: PrivatHow does a farmer's son come up with the idea of becoming a clockmaker?

The fact that Rasmus Sørnes took a particular interest in clocks may have something to do with the fact that time increasingly became a central factor in his lifetime.

In 1893, he was born into a Norway without a common time, where different parts of the country operated on different time zones. The time was determined by when the sun was in the south, which led to, for example, a 22-minute time difference between Oslo and Bergen. A person traveling between the two cities would have to set the clock.

When Sørnes was two years old, Norway started following common time, based on the Earth's rotation time around its own axis. The world was divided into 24 time zones and Norway became part of the Central European time zone.

While Sørnes grew up, clocks became more and more common in Norway. With the industrial revolution, people increasingly needed to know the time, so that they could turn up for work on time.

His creative talent was first expressed in inventions on the farm Sørnes in Sola.

As a young boy, he fashioned an automatic water pump that made the farm chores easier. Among his inventions was also a small power plant for some farmers in the area. Thanks to this, two remote farms were able to benefit from electricity and running water. With these inventions under his belt, he became known in his youth as "The Wizard from Sola".

At the age of 16, he decided he wanted to use his mechanical skills to make clocks.

THE SØRNES FAMILY, 1916: Rasmus (far right, closest to the camera) looks determined. He is drawn to electricity, aiming for the new and innovative, rather than the soil on the farm. He wants to create the future.

Foto: PrivatThe defeat

Although Sørnes was praised in Sola, it was not good enough in Stavanger.

In 1910, Rasmus Sørnes was looking for an apprenticeship with the clockmakers in the town. He had most likely put on his finest clothes and referred to past achievements. Nevertheless, the answer was no, wherever he went. They said his hands were too big. That he wasn’t suited for fine mechanics.

Perhaps the real explanation was rather that he was a farmer's son?

When Sørnes applied for an apprenticeship as a clockmaker, he stretched himself and went beyond the framework that society had laid out for him. He was expected to keep his eyes and feet on the ground and stick to his own class. Not mingle with clockmakers, who were higher up the ladder.

Many would perhaps have returned to the farm, making do with working the land, but Sørnes would be damned if that was to be his lot. If he couldn't work with clocks, he would work with electricity. He became an apprentice electrician. At the same time, he attended an elementary technical school for one year, and in this way acquired knowledge about technical drawing, mathematics and technology.

DRAWING TALENT: One of many sketches that Rasmus Sørnes drew for his clocks.

Foto: Nima Taheri / NRKSørnes got married, had children and got a job as a radio technician. He was a hard worker who rarely had time for a break; in his spare time, he and his wife started their own radio station, which may have been the first in the country. Sørnes read the news and weather reports while his wife read poetry.

He went on with his life without having acquired the title of clockmaker.

WITH HIS FAMILY: Rasmus Sørnes with his wife and children in 1926.

Foto: PrivatThe man at the lighthouse

How did he become a clockmaker after all?

In 1931, Sørnes got a job at Jeløy Radio in Moss. He built a house and moved to the island with his family.

At the radio station, his job was to look after all the technical aspects, but he was also responsible for the lantern on a lighthouse outside Jeløy. There, among other things, he made a solar cell that charged the battery on the lighthouse.

He had many night shifts. Between tasks, perhaps he was lying down gazing up at the starry sky. Was this the place where the idea for his life's work came to him? We rarely think about it, but the clocks we constantly follow derive their time from movements in space.

DETAIL: The sun and moon hands move across the twelve zodiac signs.

Foto: Nima Taheri / NRKAt the age of 41, Rasmus Sørnes took up his childhood dream again. He wanted to make clocks that showed us the connection between the starry sky and our lives. In 1934-1935 he decided to build his first astronomical clock.

In the 1930s, clocks became increasingly smaller in size, but the clocks Sørnes now created were large and heavy. Astronomical clocks contain much more information than just the time and date. Imagine these clocks as a real-time model of the solar system. The starry sky on the clock shows the same as you see if you look up, and you get an understanding of, for example, how high and low tides are linked to the movements of the moon.

This was also a type of clock that was beyond the capacity of most clockmakers. Was this his own brand of vengeance?

How to build a clock

With the clocks, Sørnes was able to combine all his interests and abilities. Time. Astronomy. Electronics.

The new job at the lighthouse meant some days on and some days off. On days off he built his own workshop. There was less time for family life.

The preparatory work for the astronomical clocks was extremely thorough. "I first familiarized myself with the necessary astronomy, and that was not that straight forward," he later wrote in a note. He learned higher mathematics, as well as German to read astronomy books, and he wrote letters with questions to professors. Then he had to find out what functions the clock should have and calculate the correct data that he could feed into the clock's construction.

The calculations could look like this, for a single function:

He then drew the clock with its hundreds of parts.

And then he had to make the tools and machines with which to make the clock. He didn’t have access to clockmaking tools.

Only after all this the construction could begin. And he set to work fixing small parts together with his big hands.

The first clock was built within a year. This clock seems to have been intended as a test all along. Here he concentrated on certain functions such as tides, the movements of the moon, leap years and the starry sky.

THE FIRST: Clock number one.

Foto: Erik ØdegaardA person who is going to build a clock will quickly become familiar with problems with our time measurement. In a clock, the gears tick steadily, based on calculations of the movements of the Earth and the sun. It's just that the movements of the universe are in reality unstable, which means that not all days are the same length.

Rasmus Sørnes was unable to adjust for the uneven movements in clock number one. Nevertheless, he must still have thought that there was potential here, because he quickly set to work on clock number two.

The second attempt

In clock number one he had relied on information from the almanac, but now he no longer trusted it. The observations were too inaccurate, he wanted to double check for himself. So, naturally, he decided to make his own telescope.

The telescope became Norway's second largest.

BINOCULARS OR A CANNON? During the war, Sørnes was forced to dismantle the telescope. The reason? The telescope was so heavy that it looked like a cannon. The neighbours were afraid that it would get bombed by planes.

Foto: PrivatDespite this feat, Sørnes wasn’t satisfied with clock number two either. The various parts were too tightly packed together and important discs and movements were too small.

CLOCK NUMBER TWO: With a globe on top.

Foto: Rasmus SørnesIn addition, he had a problem with the Gregorian calendar. Here we’re talking about extremely complicated calculations, but in short, the calendar doesn’t add up, even if leap year days have been entered. Three times every 400 years a leap year must therefore be skipped. It seems abundantly clear that Rasmus Sørnes wanted this perfect in his clock!

Therefore, he began again. Clock number three was underway.

Rasmus Sørnes i verkstaden sin.

The masterpieces

Clock numbers three and four are considered some of the world's most complicated clocks. They are identical in functionality; the difference is that clock number four is more beautiful than three.

CLOCK NUMBER THREE: Is today displayed at the Borgarsyssel Museum. The clock doesn’t run, due to maintenance.

Foto: Nima Taheri / NRKIn these two clocks he managed to solve many of the problems with uneven time measurement that he had struggled with. At the same time, the work consisted of getting the different parts correct in size and fitting the clock together as a whole. Because a clock is like a person. Everything is connected. Kidneys, liver, intestines. If the kidneys fail, everything fails.

That is why there is a special backup solution for power interruptions on the clocks. Sørnes created a back-up solution to ensure that the clocks would still run during a power cut. When the power is restored, the clocks automatically go back to being electrically powered again. In this way, the Sørnes clocks can keep things going through almost anything.

At the bottom of clocks three and four he placed a loudspeaker where a self-propelled cassette tape played instructions about the clock. Sørnes clearly didn’t think that he had a good enough voice to read the instructions himself, so he hired an actor.

CLOCK NUMBER THREE: At the bottom center is the loudspeaker.

Foto: Nima Taheri / NRKIt is touching to see all the small beautiful details he has thought of. The hands are adorned with a sun and a moon. A separate moon is white on one side and black on the other, so that when the clock is running, the moon will move from full to half.

SVEIP: Detaljar frå Rasmus Sørnes si klokke

Finally, the clock was gilded with his wife's gold jewellery, and Sørnes engraved it neatly on the outside.

Clock number three was completed in 1954, clock number four in 1966.

CLOCK NUMBER THREE: The Sørnes clocks are among the last manually made astronomical clocks in the world. After this the factories took over.

Foto: Nima Taheri / NRKAt 73 years old, Rasmus Sørnes had finished his life's work and the clocks were placed in the basement. He got himself a new hobby. An aquarium.

In Borgarsyssel Museum there is a note in which Sørnes himself summarizes his life. There he writes: «Finally, I can say that the dream of working as a clockmaker that I had in my youth has come true after all. The only thing that remains is to hope that things will turn out in such a way that the public can benefit from it.»

Still, very few have heard of Rasmus Sørnes.

Why didn’t he become more famous?

He spent all his time on these clocks, but people found it difficult to take in what he had actually created. His family tried to offer the clocks to a couple of Norwegian institutions, but were turned down.

Maybe it was because he didn't like talking about himself? He was capable of creating the most wonderful things, but he was not a good salesman. Furthermore, he didn’t have the status of a clockmaker, a professor or someone of their ilk.

In the 1970s, clock number four disappeared to the United States. The American Time Museum realised the value of Sørnes' clock.

In Norway, the clocks were forgotten until clockmaker Erik Ødegaard showed up. The 76-year-old Sarpsborg local is passionate about clock history.

CLOCKMAKER: Erik Ødegaard is very impressed by what Rasmus Sørnes achieved. He has spent many years of his life trying to bring the clocks to light.

Foto: Nima Taheri / NRKFor 16 years, he spent his summer holidays traveling around Europe looking at the most beautiful, most complicated clocks. His surprise was all the greater when, at the end of the 1980s, he discovered that some of the most beautiful clocks were located in his immediate environment – on Jeløy.

Ødegaard eventually had clock number three, which was at Sørnes' daughter's home, moved to the Borgarsyssel Museum. The clock is on display there today.

– Sørnes’ project is historically unique in both clockmaking history and cultural history. There is no equivalent in the world. He set himself the goal of creating a project that is far above what ordinary clockmakers can do, says Ødegaard.

He wants to emphasize how special it is that one person could do all this. That we must learn from Sørnes who did not give up and who on his own accord acquired the knowledge he needed to create something unique.

Gradually, Sørnes gained honour in professional circles. Among other things, engineer Erik Tandberg, who famously commented on the moon landing for NRK in 1969, wrote an article in which he described Sørnes as a unique multi-talent who was able to accomplish an incredible amount at a high level with few resources.

Before Rasmus Sørnes died in 1967, he also got to experience admiration from clockmaking circles. Young clockmaker apprentices came to look at the clocks. He who was self-taught, now found himself teaching.

IMPRESSED: An elderly Rasmus Sørnes shows one of the many sketches he made while working with the clocks. Clockmaker apprentices line up to watch.

Foto: PrivatPS: When clock number four was sold at auction in 2002, it disappeared from public view. The buyer wanted to remain anonymous. Erik Ødegaard has created the website haveyouseenthisclock.com where he asks for leads.

Sources: «Klokkemakeren Rasmus Sørnes» by Tor Sørnes, Sola historielag, Erik Ødegaard, Borgarsyssel Museum, Ruth Tjensvoll and Eivind Tjensvoll, Store Norske Leksikon about tid and astronomi.

English translation by Tone Sutterud.

Read the story in Norwegian: Tidenes revansj

Hei!

Do you know the whereabouts of Rasmus Sørnes' clock number four? If so, please do get in touch by clicking the button next to my name (meaning "Send me an e-mail"). NRK is interested in locating the clock for a possible follow-up.