What’s going on in Jenny’s mind?

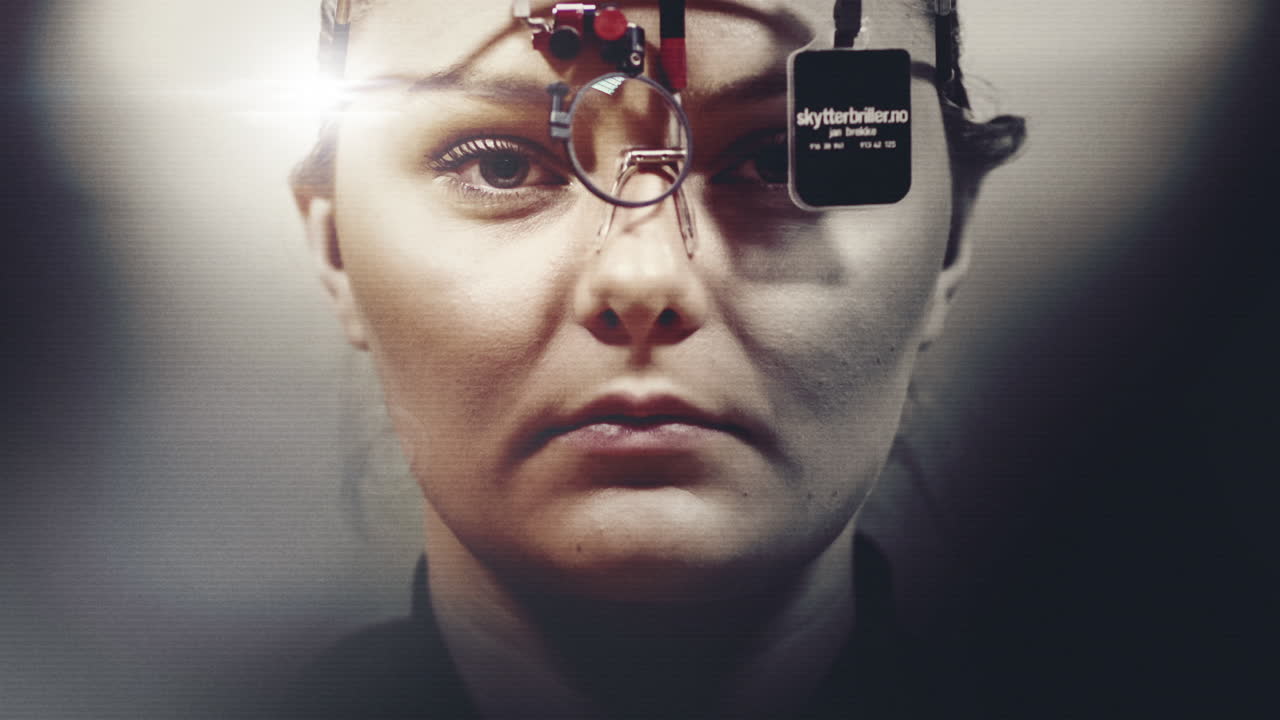

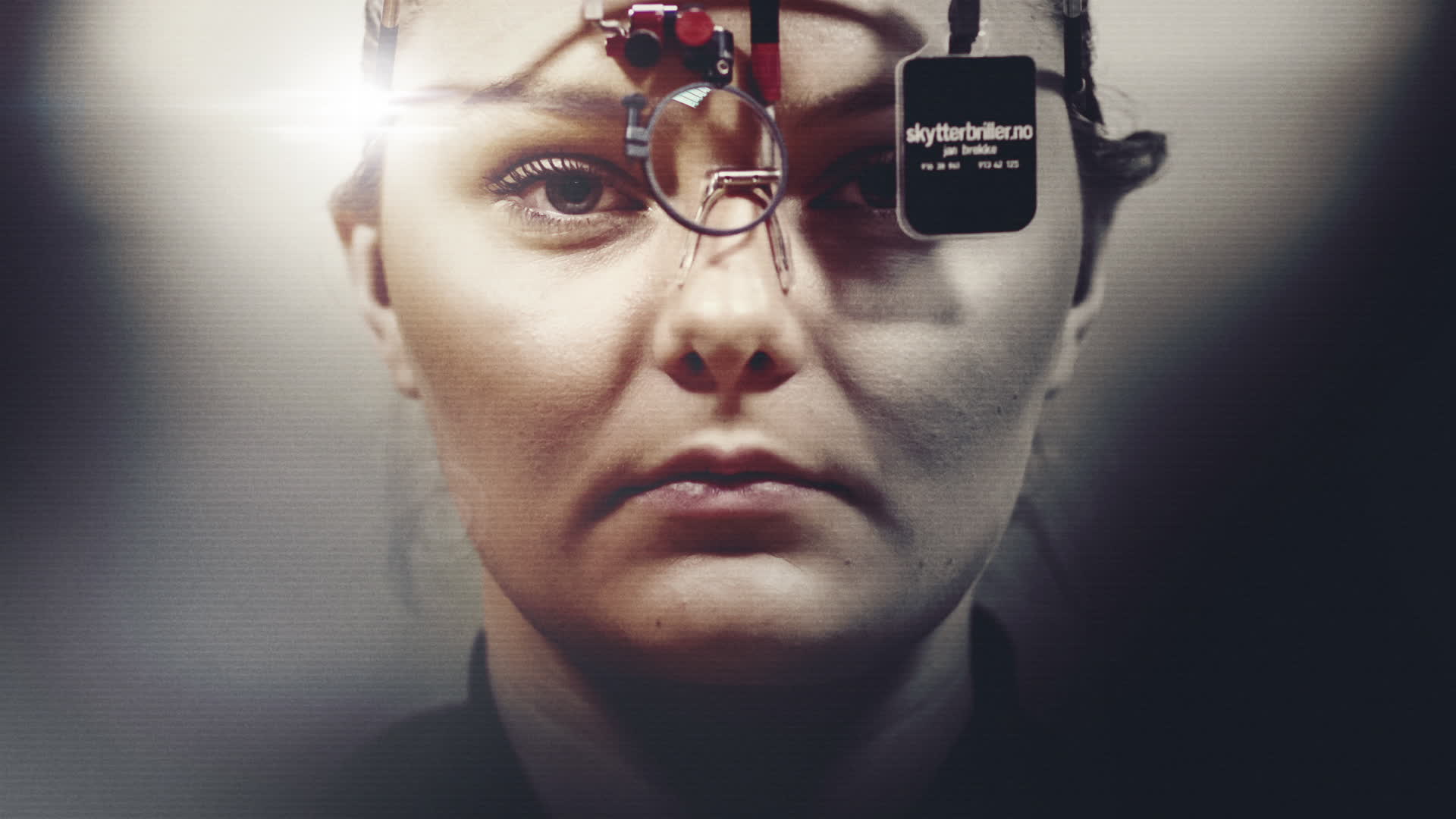

The super-talent Jenny Stene pushes the envelope and breaks records. They say there’s something about the mind of the rifle shooter – something that could be useful to many.

– Maybe you can find out what’s going on with Jenny?

We weren’t expecting the question.

Sports manager Tor Idar Aune sat facing us in a conference room at the Norwegian Shooting Federation.

We’d gone through the list of participants on the national shooting team, and been told about one medal candidate after the other, because that’s how good Norway is at shooting these days.

Now we’d reached one of the real stars on the list. Jenny Stene. 22 years old, rifle shooter and world record holder.

– Find out what’s going on with Jenny?

– Yes, Aune says. He chuckles. The sports manager tries to avoid superlatives, but this time it’s not easy.

He’s thought about it for a long time, he says, ever since Stene joined the national team two and a half years ago and started doing things they’d never seen before.

Her stratospheric performance was one thing. That was sensational enough in itself. But that frankly wasn’t what he was thinking about right now.

The sports manager said that in competition, Stene can enter a mental state that others around her don’t quite understand.

– There’s something about Jenny. About her mind, Aune said.

He told us why he thinks it’s so crucial.

– I think that if you can find out how that mind works… A lot of people could learn something from it, even ordinary people who don’t take part in sports, said Aune.

That’s how it started.

Could everyone actually learn something from this mind?

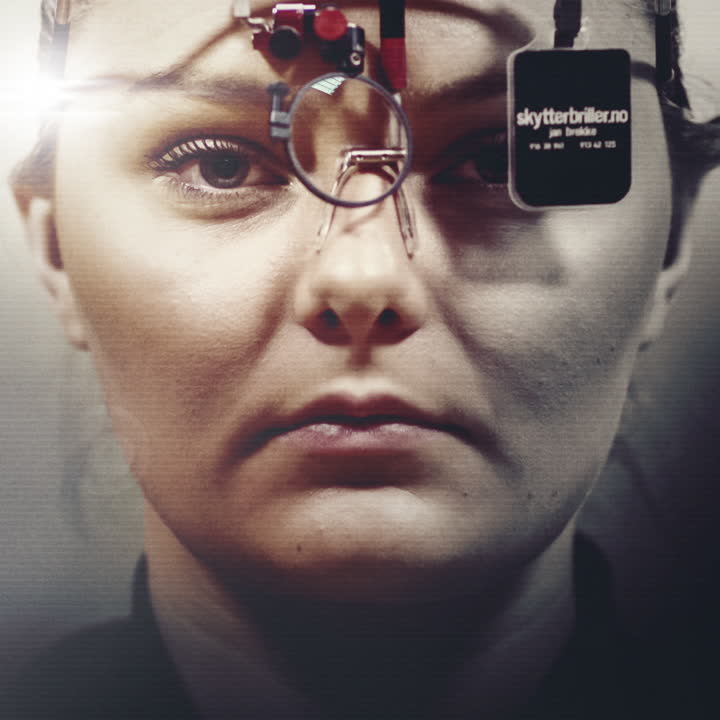

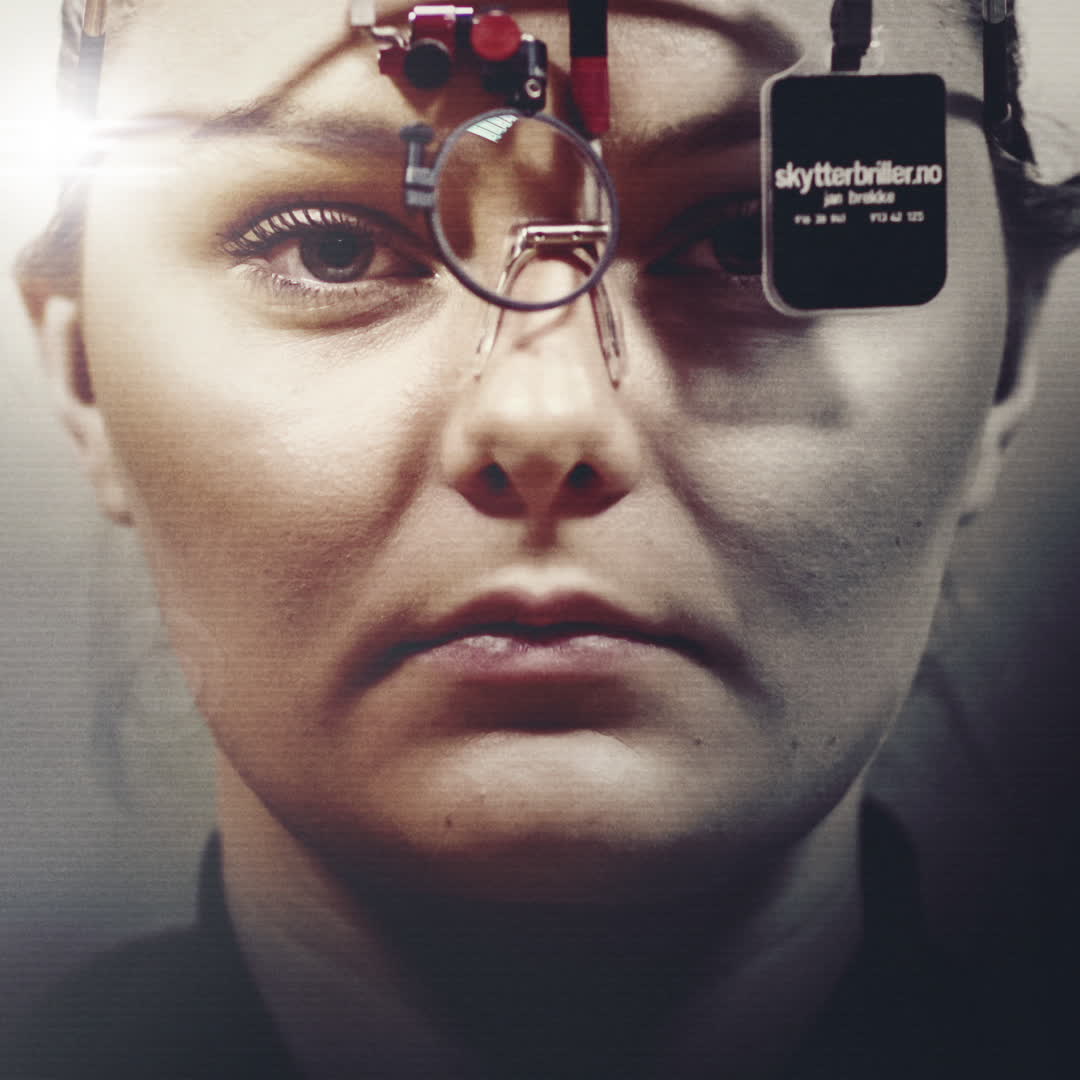

Foto: Erlend Lånke SolbuFearless

We meet her for the first time early one morning in the basement of the Norwegian School of Sports Sciences, where the national shooting team usually trains.

Jenny Stene giggles when we ask her what she thinks about our slightly unusual request, whether we might try to find out what’s going on in her mind.

– It’s intriguing. I’m curious myself, she says.

Stene started her shooting career at home in Kisen, and has been regarded as one of the world’s greatest talents since she was a teenager.

Stene is one of the world’s best rifle shooters. She started shooting at the age of nine because her brother and the boy next door were into it.

She discovered that there were two things she particularly liked about the sport: That she immediately mastered it, and that it felt “kind of awesome” to do something different. Then and there, at the age of nine, she decided to become the best.

At the age of 19 she came out with a bang, winning third place in the World Cup, and last year she won a bronze medal in the European Championships.

The past ten years she’s specialised in two events, 10 metre air rifle and 50 metre rifle three positions, the shooting equivalent of a marathon on where you fire a total of 120 shots from a kneeling, prone and standing position.

But when the others say Stene has something that makes her stand out, it’s not only her flawless technique they’re talking about. We hear it again and again.

– If you wanted a prototype fearless person, it would be Jenny, says national team coach Espen-Berg Knutsen.

Absolutely fearless. Totally awesome, says sports manager Aune.

And top rifle shooter Henrik Larsen:

– Jenny’s fearless. She just ploughs through, doesn’t care, doesn’t think about the consequences.

There’s a reason why they’re so intrigued by her fearlessness. There’s a common problem in shooting sports.

Shooters are prone to sudden meltdowns. Nerves that go awry, a runaway heartbeat, complete mental collapse – and competitions that end in failure. It can happen in other sports too, but it’s important to understand this: In shooting it’s a hallmark of the sport.

– I’d say it happens to someone in every single competition, Henrik Larsen says.

People in the know say that this sports is at least 80 % mental. The story of Matthew Emmons is often highlighted as the best, or worst example of how true this is.

The champion that collapsed

The American Emmons was seen as the best rifle shooter in the world for many years. But then he reached the Olympic finals in 2004.

Emmons was ahead in the finals, as expected. Only the last shot remained. That’s when it happened: Emmons shot the wrong target and hit his challenger’s bullseye instead of his own. An incredible howler.

He lost his focus for a split second, and it was more than enough to ruin absolutely everything. That single error made him end up last in the finals.

Emmons has just realised that the gold has slipped through his fingers because of an error that would haunt him for years.

Foto: DOUGLAS C. PIZAC / ApAnd that’s not the end of the story. Four years later, it repeated itself as Emmons once again was ahead in the Olympic finals, and only had a single shot left.

This time he hit the right target, but he still had another meltdown. The shot was unbelievably poor. He only got 4.4 points. At his level, anything under nine is extremely unusual. Once again the gold slipped through his fingers.

Shooting is a sport that requires such a high level of physical and mental calm that it’s difficult to describe it in words.

To give you some idea: Shooters are trained to fire between heartbeats, because even an imperceptible thump of the heart can generate enough movement to miss the target.

This is how still and steady you have to stand. Like a granite statue.

Members of the Norwegian National Shooting Team exercise upwards of 1300 hours a year. A lot of the exercise looks like this: For 20 minutes they stand completely motionless while they aim, either at the wall or directly ahead. This is how they build up both balance and sight.

Foto: Erlend Lånke SolbuIn other words, shooters should never be nervous, because they should never have a high heart rate. And tremors have to be avoided at all cost.

But imagine competing under that kind of pressure. Wouldn’t it have made you nervous and shaky?

When shooters fail, the reason is almost always mental.

So the sports manager’s challenge to find out what’s going on with Jenny Stene was an opportunity to explore uncharted waters. A different kind of edge and fearlessness than what we most often encounter in the world of sports.

One that isn’t connected to handling external risks and dangers, but coping with what’s on the inside.

The state

There’s only one sensible way to do this, and that’s to find someone who knows everything about the brain. That’s why Stene is about to meet neuropsychologist Thomas Myklebust, an expert on the two parts of consciousness we have to explore: The biology of the brain as well as the psychology of the mind.

– It would be brilliant if it could help make me even tougher, says Stene and smiles.

She can’t help giggling when she hears that others call her fearless.

– But, yeah… I know that I can go into a sort of “state”, she says.

We’ve heard a lot about this, because when she’s there, others notice.

There’s especially one story we hear again and again.

The historic day

It was 28 May 2019.

The national shooting team was in Munich in Germany to take part in a major competition. Stene started the day by watching her teammate Katherine Lund unexpectedly break the Norwegian record.

Everyone was happy and jubilant. I thought it was really cool. So… I decided to try to match her, Stene says. She laughs.

Those present when Stene competed later the same day, all tell the same story:

She shot in a way that can best be described as robotic. She simply hammered the target, again and again, 120 times, at a wild pace. She was incredibly fast.

– She was brimming with self-confidence. She seemed to have made up her mind. The speed took your breath away. And she was hitting the bullseye again and again and again, her national teammate Henrik Larsen remembers.

Time doesn’t count in this event, so there’s not really any point in shooting rapidly.

But Stene shot like lightning anyway, because that’s what she does when she’s there.

She finished at a record 1 hour and 35 minutes – half an hour quicker than most of the others.

Then Stene heard the roar from her teammates. She wasn’t aware of her score. Henrik Larsen had to tell her:

– “You know you’ve broken the world record?”, I heard him say.

The scoreboard read 1185 points. Three points past the previous world record. Outclassing everyone else.

And at the time? Nobody had seen anything like this.

– I’d say she broke two records, both for points and time, Larsen says.

She was 20 years old, competing against people who’d been doing this for 15 years, winning medals and everything. Then this upstart from Norway turns up and steals the show. It’s almost impossible to describe the level of this achievement, he says.

Henrik Larsen and Jenny Stene are two of Norway’s greatest shooting talents.

Foto: Erlend Lånke SolbuSat gaping

There have been many other astounding achievements as well. Like that one time in the European Games, when the competition was outdoors, and a violent wind started blowing.

– You could only shoot exactly when the wind turned, and the window was only three or four seconds. You had to shoot at the exact point you saw the window, says national team coach Berg-Knutsen.

Many were petrified by the almost impossible task. But almost every time the wind turned, there was a crack from Jenny Stene’s rifle. And not only that: She hit the target.

– I just sat there gaping. I thought, “Is this even possible?”, the coach says.

That’s what makes people so curious.

When the going gets tough, and everyone else would get nervous, Stene just shrugs. It’s as if the challenge triggers something in her. And then there’s her stratospheric performance.

And doesn’t it look like it all starts in her mind?

Something happens on the shooting range

Is it possible to simply decide to be fearless? Summoning a state that gives you an invincible power? In many ways, the answer is yes, says neuropsychologist Thomas Myklebust.

– It’s something you can develop through training, and then practice triggering it as needed through various techniques, he says.

Thomas Myklebust is a practising psychologist and specialist in clinical neuropsychology. He also travels around Norway giving lectures about the brain.

Foto: Håkon LexbergIs this what Stene has achieved?

She doesn’t seem to be conscious of it herself. She thinks she simply has what she calls an “extremely competitive streak”.

– I want to be best at everything, even if it’s just a board game, Stene says.

But most top athletes are extremely competitive, so that can’t possibly be the whole answer.

Stene carries this notebook with her wherever she goes. She writes down everything, from how her training went, to what her goals are – day by day and long term.

Foto: Erlend Lånke SolbuWe should point out that Stene isn’t “robotic” all the time. She can get nervous, especially before finals.

But she’s revealed something that seems important. When she manages to find the right mode, it clicks in fairly late. More specifically: As she takes the stand on the shooting range, just before the competition starts.

– That’s when my mind goes blank. When I’m there, that’s when I shoot well, she says.

When neuropsychologist Myklebust hears this, he nods. It’s something he recognises. It means that the mode is situational.

That’s often how it is with the mind. It’s a bit like a muscle: It’s good at what it practices. This is why people can develop extraordinary abilities in certain situations or settings – that they don’t necessarily possess otherwise in life.

It also means something else. Now we know how to trigger it, whatever it is that Jenny Stene has.

We have to take her to the shooting range.

The stress test

Together with Myklebust, we’ve set up a minor experiment.

– It’s not really a scientific experiment, because then we’d have to be more thorough, but hopefully it may give us a pointer about what’s going on with Jenny, Myklebust explains.

Stene is going to shoot some series more or less like she does in a competition, but with a tiny twist: We’re first going to make her nervous, and measure her heart rate all the time.

– It would be interesting to see whether she actually has the ability to control her heart rate, says Myklebust.

We measure her heart rate for a while before we start, and Stene has a slightly higher natural heart rate than average. It’s usually just above 90 bpm when she’s at rest.

We’ve gathered information from her teammates: Mental arithmetic and riddles make Stene nervous, they said, and added; bring a TV camera for maximum effect.

Thomas Myklebust does his best to get Stene out of her comfort zone. He begins with some arithmetic from primary school.

Then he moves on to the riddles, which have a visible effect. Her heart rate increases.

On the neuropsychologist’s orders, Stene starts firing a series of shots.

That’s when we see it.

At first we wonder whether it might be a coincidence, but it happens again and again.

Inner peace

Every time Stene pulls the trigger, the heart rate monitor shows the same thing: Immediately before the shot, her heart rate falls by 10–20 bpm, several times all the way down to 80–82 bpm – i.e. lower than when she’s at rest.

What’s most striking about it is that her heartbeat just stays low exactly the time it takes to deliver the shot.

Once she’s pulled the trigger, it jumps back up again to normal, and stays there until she prepares to fire another round. It starts dropping again just before she shoots.

Stene is slightly surprised to hear this. She’s never measured her heart rate on the firing range before.

And she’s always thought of this inner peace she achieves as a fuzzy feeling. Then it turns out to be something very tangible.

So how does she manage to lower her heart rate like that?

– It’s extremely powerful. It’s the head of the brain, so to speak, Myklebust explains.

– Feelings, for example. We often assume they live a life of their own. But we can control them with the frontal lobe, Myklebust says.

The frontal lobe can help us with many things – if we only manage to activate it. Like keeping calm during competitions.

And in theory: Lowering the heart rate.

There’s just one problem.

The result can be what happened to the unfortunate American shooter in two Olympic finals.

The good news is that we can all learn to ease our fear when the amygdala rears its head.

And there’s every indication that this is precisely what Stene has learned to do.

Two magic words

When Myklebust and Stene sit down for a long chat to really get to know each other, the whole story comes to light.

Myklebust and Stene kept talking for 90 minutes.

Foto: Lars Thomas Nordby– What do you do when you get thoughts that don’t belong in a competition? Myklebust asks her.

– I breathe, says Stene.

– And then they go away?

– Not always. But then I have my triggers.

– And what are they?

– We’ve decided that I should have two triggers in a finals situation. I think “breathe” and then “hold”.

Breathe and hold. Stene repeats these words in her head as she competes. She’s chosen them carefully.

When she thinks “breathe”, she enters the calm, even rhythm of breathing she’s practised in advance. Then she thinks “hold”, which is the phase after she’s shot, where she remains standing there in the same position for a moment, holding the rifle.

These are two words Stene associates with something tangible – and positive.

What she does when she repeats the words, is using a well-known psychological technique: She replaces any fear and stress with something else.

– You can do it with some practice, Myklebust explains.

Through what she calls trigger words, Stene summons the head of the brain: The frontal lobe. It activates when she focuses on words, and thus helps her stay focused and calm. She overrides her nerves before they take charge.

This is what’s going on in her mind when other people think she looks like a fearless robot.

Anyone can learn

It was exactly as sports manager Aune thought: A lot of people can learn something from Jenny.

– Everyone can actually learn these techniques. And they can basically be applied to all sorts of life situations. The trick is to identify the words or thoughts that work for you, Myklebust says.

When Stene broke the world record, she was repeating her triggers. But she has to add that she’s also repeated her trigger words endlessly sometimes, and still felt stressed.

– It’s not easy to pull it off every time. It may be especially hard during finals. Then you’re prone to blacking out, she admits.

A DAY AT WORK: The shooters stand completely still holding their weapon for many hours every day. Mobility training is required.

Balance training is even more important. Here’s Stene doing balance warmup in Munich. She takes these curved woodblocks with her wherever she goes.

Warm-up is generally a little different in shooting than in other sports. Here, Stene warms up the gaze and the ability to aim. She aims straight at the wall - preferably for 20 minutes.

But the most important thing with the warm-up is actually to fool around, the Norwegian shooters believe. This makes them a little less nervous.

This event in Munich is like an annual mini-Olympics. All the best shooters come here.

This year, things did not go so well for Stene. She struggled with her balance (which happens to most people from time to time), and this affected her in the competition.

It is only when you see it in reality that you realize how small the target is.

Despite losing early, Stene managed to shoot several 10.9 shots. That is the highest score.

Stene has high ambitions, and shed a few tears when the competition didn't go as hoped.

But she will not let disappointments linger for too long: Already a few seconds later, tears had turned to laughter.

The question we really should ask

Stene isn’t the only one who uses trigger word techniques. It’s a well-known method in top sports. Maybe the question we really should ask is this:

Why does Stene in particular benefit so much from them?

– I think I’m good at not complicating things. That’s just how I am. I’ve always been like that, she says.

But there’s another thing. Stene feels secure in the sense that she isn’t that afraid of failure.

– I really want to do well, but it’s no disaster for me if I score nine instead of a bullseye. I just get back on top and focus on the next shot, she says.

This is where we have to take a look around at everything and everyone around Stene. The people who maybe, and possibly without thinking about it, have helped shape Jenny’s mind.

The mental journey

The past five years, the national shooting team members have been on a kind of mental journey together. Both sports manager Aune and coach Berg-Knutsen had been newly appointed, and they realised they had to take the psychological side of sports even more seriously.

Among other things, the team got its own sports psychologist.

Every Tuesday, Anne Marte Pensgaard from Olympiatoppen, the Norwegian resource centre for top athletes, comes by for national team training. The team members imitate competitions, and every time, Pensgaard adds new factors to create stress. Once she brought an entire school class who bet on which shooter would win.

Everything to try to prepare the athletes for the stress they encounter in real competitions.

And the team have agreed to completely stop talking about results. Instead, they have other goals.

– Like for example that we shall be best technically, basically best at everything that can make us the best. We believe that when the athletes know that we don’t focus on their results, they avoid the extra pressure this may create, says sports manager Aune.

Sports manager Tor Idar Aune helped nudge the national shooting team in a new direction five years ago.

Foto: Terje Bendiksby / Terje BendiksbyThe shooters are so stubborn on this point that they’re the only sports federation that’s refused to deliver concrete achievement goals to Olympiatoppen about how they aim to perform in the Olympic Games.

There’s also one final thing. If you’re going to be part of the Norwegian national shooting team, you have an extra responsibility that’s just as important as hitting the bullseye: Making sure that everyone else is okay.

– We don’t budge an inch when it comes to team spirit, says Aune.

There are three female rifle shooters on the national team, all at the same top level. The two others are Jeanette Hegg Duestad (left) and Katherine Lund (right).

Foto: Erlend Lånke SolbuAll this to create a sense of community that in turn creates security.

And it certainly seems like the way to get good shooters, because during these past five years, Norway has brought forth a young team that’s begun to dominate. Stene is just one of several national candidates for a medal in the next Olympic Games.

Still needs practice

– Most of this is textbook psychology, Myklebust concludes.

– Jenny knows how to simplify things. She manages to avoid complicating things for herself when it starts to boil over, he says.

– The other thing is the way she says she empties her mind and switches to autopilot. This is something she can develop further.

Because as of now, Stene doesn’t automatically switch to “robot mode” in every competition.

– But as we look forward, it’s about making it even more automatic. Then I think she’ll handle it, even when she faces blackout in a final, says Myklebust.

Stene nods.

– I just have to practice this as much as I can, she says, and ends with a conclusion that has to be the epitome of simplification:

– I guess I just have to make sure I get to as many finals as possible, she says and grins.

Originally published in norwegian 11 july at 08:12 am as part of the article series The Science behind the Medal.